Mistletoe: Parasitic Plant to Party Décor

Its botany is indeed fascinating, and we’ll get to that, but let’s start with its history. Mistletoe’s use goes back at least as far as the ultra-practical Greeks, who used it as an herbal treatment for cramping, epilepsy, ulcers, and as an antidote to various poisons.

Admittedly, not very romantic. At least, not until the Celts. Celtic druids (arguably among the world’s earliest naturalists) famously attached mystical meaning to many plants and trees. Mistletoe, because it blooms in winter, was seen as a sacred symbol of life, vitality, and fertility—one possible origin of its romantic connotations.

Interestingly, Norse mythology could also make this claim. (This story is a bit challenging to follow, but stick with me.) The god Odin had a son, Baldur, who was prophesized to die. In response, Baldur’s mother, goddess of love Frigg, petitioned every plant and animal to promise they wouldn’t hurt her son. Unfortunately, she neglected to consult with mistletoe, which was used, eventually (and convolutedly) to kill him.

Frigg, however, was able to bring her son back to life, Snow White-style, with a kiss. So happy was she, Frigg decided mistletoe would be a symbol of love and vowed to kiss anyone who happened to pass beneath it. (There are other versions of this story where Frigg’s tears turn into mistletoe berries that bring Baldur back to life, but it all adds up to the same result.)

Shirley Wynne, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Okay, great. But when we try to jump from medicinal/symbolic plant to party decoration, it gets a bit murky. One theory for its connection to Christmas comes from a common Medieval Christian belief that mistletoe was once a tree. Because this tree was allegedly used to supply the wood for Christ’s cross, it was condemned to become a parasitic vine and, as penance, to bless anyone who walked beneath it.

In Scandinavia, mistletoe was believed to be a symbol of peace and reconciliation, the perfect arbiter of truces. From this belief sprang the tradition calling for fighting couples to lay aside their arguments and “kiss and make up” under mistletoe.

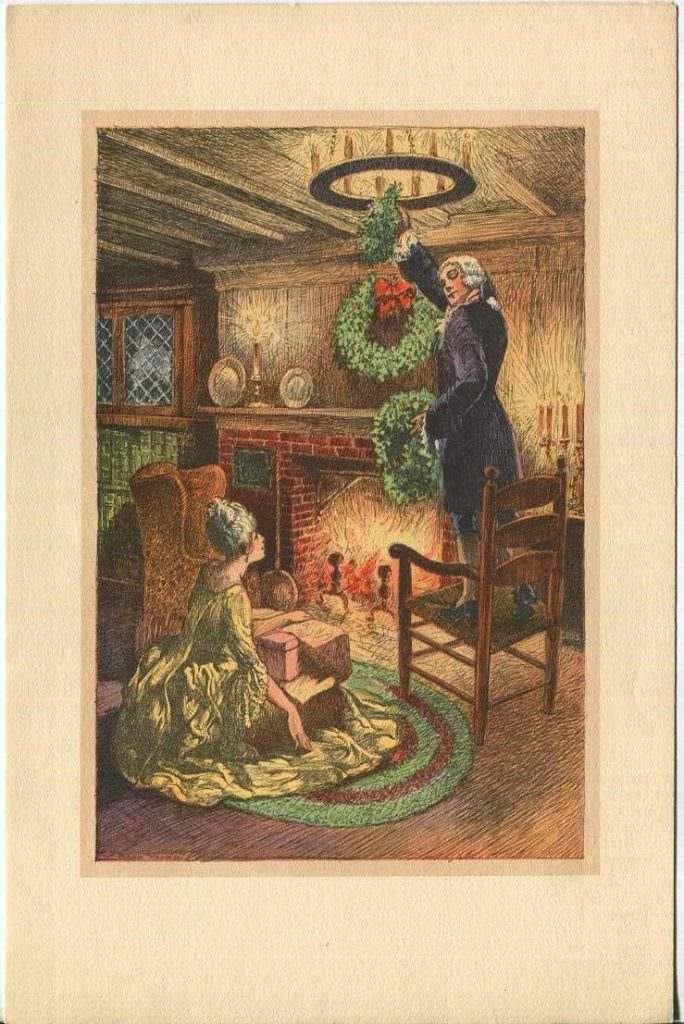

Somehow, all of this made the jump into the pop culture of 18th-century England’s serving class, and that’s when the “kissing plant” really took off. According to the “rules,” a woman standing under mistletoe could be kissed by any man, a kiss it was bad luck to refuse and good luck to accept. Every time someone used the plant for this purpose, a berry was picked until none remained. You can find mention of this tradition in Washington Irving’s Christmas Eve (1820) and Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers (1836).

William Mark Young, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tempted to add mistletoe to your seasonal décor? Maybe its intriguing botany will be the deciding factor. First, there are several varieties of mistletoe. The one I’m referring to in this article is European mistletoe, Viscum album, a parasitic plant (technically hemiparasitic, meaning it performs limited photosynthesis) that gets most of its nutrients from the plant or tree it’s rooted to. This mistletoe completes its entire lifecycle without ever touching the ground–definitely unusual for a plant. But it’s also considered a pest of both conifers and deciduous trees. Trees parasitized by mistletoe have shoot die-off and become more susceptible to fungal and bacterial diseases. (As a side note: we do have mistletoe species in North America—American or oak mistletoe, Phoradendron leucarpum, is found throughout the southeast and as far north as New York.)

Not the most romantic of roots (forgive the pun) for a holiday tradition, I know.

Or maybe it is… Mistletoe, parasitic and destructive to trees it may be, is also considered a “keystone species,” meaning it plays a positive supporting role in biodiversity. Birds feed off the berries (spreading the plant as a result), and areas with high mistletoe density have been found to support a wide spectrum of animal diversity. (Ecologist David M. Watson writes about a related Australian study here.)

A complicated history? Sure, but think about the conversations it could start at your next party. Who knows what romances could crop up and thrive over the coming year?

**Many thanks to Katherine Brewer, the Gardens’ incredibly knowledgeable Curator of Living Collections, for her help on this article.